A celebration of “Worldwide Mifune.” Edited from an original piece for Turner Classic Movies that is languishing somewhere in the bowels of the internet.

Toshirō Mifune was born on April 1, 1920 in Tsingtao, China (now Quingdao, Shandong), which at that time was under Japanese military rule. His parents, both Japanese citizens, were Methodist missionaries. They had moved to Tsingtao as part of a coordinated effort by the Japanese government to encourage its citizens to move into the region to reinforce its military control. Mifune’s father was also a photographer and owned his own shop, also providing a young and eager Toshirō with the tools to learn the trade and hone his photography skills. Because he was a Japanese citizen, Mifune was drafted into the Imperial Air Force at 20 years old, despite never having stepped foot onto Japanese soil. (Which he did for the first time at the age of 21.) From 1940-1945, during World War II, Mifune’s photography training was put to good use, with him serving as a sergeant in the Imperial Air Force’s Aerial Photography Unit. Near the end of his service, Mifune was stationed with a special attack unit in Kyūshū and was responsible for the morale of the pilots assigned suicide missions. He would take a “commemorative” portrait, treat them to dinner, and offer parting advice: “Don’t yell ‘Long live the emperor.’ Go ahead and cry out for your mother. There’s no shame in it.” However, like many men who were forced into wartime service, Mifune was not at all cut out for a military career. In fact, Mifune was critical of Japan’s role in the war and was forever changed by his experiences. He detested the many years of what he called a “senseless slaughter.” When asked about his service during World War II several years later, Mifune recalled a time of great personal fear and hard, menial work saying, “These big laborer’s hands of mine are my unwanted souvenir of that time.”

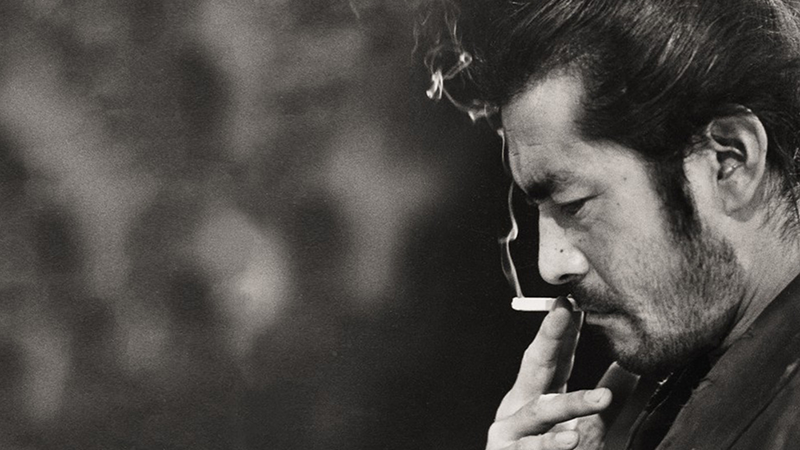

Toshirō Mifune, member of the 7th Air Brigade of the Imperial Army Air Service

After the war, Mifune moved to Tokyo in hopes of finding a photography job. One of Mifune’s friends worked at Tokyo’s Toho Studios and encouraged him to apply for a position as an assistant cameraman. Instead, Mifune found himself auditioning for the studio’s “Wanted: New Faces” talent search. It was during this audition that director Akira Kurosawa discovered the man who would become his go-to leading man. When asked about how he first met Toshirō Mifune, Kurosawa said:

“A young man was reeling around the room in a violent frenzy. It was as frightening as watching a wounded or trapped savage beast trying to break loose. I stood transfixed. But it turned out that this young man was not really in a rage, but had drawn ‘anger’ as the emotion he had to express in his screen test. He was acting. When he finished his performance, he regained his chair and with an exhausted demeanor, flopped down and began to glare menacingly at the judges. Now, I know very well that this kind of behavior was a cover for shyness, but the jury seemed to be interpreting it as disrespect.”

Akira Kurosawa saw the great potential in Mifune and convinced the studio to put him under contract. Mifune made three films for the studio in 1947, including his screen debut in Senkichi Taniguchi’s Snow Trail (written by Kurosawa), followed by two for director Kajirō Yamamoto: These Foolish Times and These Foolish Times Part 2. In 1948, Mifune was cast in Drunken Angel, his first collaboration with Kurosawa. This film was important for both men as it established Kurosawa as one of Toho Studios’ top directors and set Mifune on the path to become its biggest international star—an achievement that earned him the nickname “Worldwide Mifune” in Japan. It was also the birth of one of cinema’s beloved director-star pairings, joining other legendary partnerships like John Ford and John Wayne; Alfred Hitchcock and Cary Grant; Frank Capra and Barbara Stanwyck; William Wyler and Bette Davis; Michael Curtiz and Errol Flynn; John Huston and Humphrey Bogart; and Anthony Mann and James Stewart.

Akira Kurosawa and Toshirō Mifune on the set of Sanjuro (1962)

Over the next two decades, Kurosawa and Mifune were intrinsically linked, perhaps even more so than their famous Hollywood counterparts. While Mifune often worked with other directors, including multiple collaborations with Senkichi Taniguchi, Kajirō Yamamoto, and Ishirō Honda, the same could not be said of Kurosawa and his leading men during this period. Of the seventeen films Akira Kurosawa directed from 1948-1965, all but one, 1952’s Ikiru with Takashi Shimura (another one of Kurosawa’s favorite actors), starred Mifune, who was undoubtedly his muse.

While both Kurosawa and Mifune had success outside of their collaborations, the sixteen films they made together are widely considered to be the finest work of their respective careers, including the masterpieces Stray Dog (1949), Rashomon (1950), Seven Samurai (1956), Throne of Blood (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1959), Yojimbo (1961), and High and Low (1963). Unfortunately, Kurosawa and Mifune’s partnership came to an end with the production of Red Beard (1965), during which they had a major falling out that was reportedly due, at least in part, to Mifune launching his own production company. This falling out led to an estrangement that lasted the rest of their lives. Regardless, their work together and strong friendship could never be forgotten. According to actor Yu Fujiki, who worked with both men, it was clear how connected they were: “Mr. Kurosawa’s heart was in Mr. Mifune’s body.”

Toshirō Mifune in Yojimbo, 1961

Outside of his work with Kurosawa, Mifune achieved considerable success, including starring roles in Hiroshi Inagaki’s The Samurai Trilogy (Musashi Miyamoto [1954], Duel at Ichijoji Temple [1955], and Duel at Ganryu Island [1956]); Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom (1966), and Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Life of Oharu (1952). Mifune also starred in several Hollywood films, including John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix (1966), John Boorman’s Hell in the Pacific (1968), and Jack Smight’s Midway (1976). In 1963, he launched his own production company, Mifune Productions, which was behind the release of over a dozen films, including Kobayashi Masaki’s masterpiece Samurai Rebellion (1967), in which Mifune also starred. By the 1970s, Mifune’s popularity with international audiences faded, but he did have a career resurgence, particularly with American audiences, with his role as Lord Toranaga on the television miniseries Shōgun, based on James Clavell’s 1975 novel. Mifune continued to work throughout the 1980s and well into the 1990s, with his final film Deep River (1995), released two years before his death in 1997.

Mifune was not only one of the most recognizable faces in Japanese cinema, but he was also an inspiration in Western pop culture. He influenced actors such as Clint Eastwood, who channeled Mifune’s rōnin character in Yojimbo in Sergio Leone’s Man with No Name trilogy. Filmmaker George Lucas was also influenced by both Mifune and Kurosawa, which is clearly evident in Star Wars (1977), featuring a storyline that is heavily borrowed from The Hidden Fortress. Lucas even asked Mifune to star as the aging Jedi Obi-Wan Kenobi or the menacing Darth Vader, but we all know how that worked out.

Toshirō Mifune in The Hidden Fortress (1958) and quite possibly what he looked like when he turned down George Lucas’s offer to be in Star Wars

Of his work with Hollywood directors and actors, Toshirō Mifine was once asked, “Now you’re working with foreigners. Dealing with them is easy for you?” With a smile on his face Mifune replied, “Well, people are people, regardless of nationality, so it’s no different to me.” That progressive approach to working with all kinds of people, as well his dedication to his craft and loyalty to his fellow collaborators, solidified his status as one of cinema’s most important and recognizable icons. Toshirō Mifune was an original. A trailblazer. The epitome of cool in a way that never has, nor will ever be replicated. His performances have never been out of style, even those where he played characters from a distant era – and that is why audiences still love him today.

Yeah, he’s definitely no April Fool.

Interview with Tetsuko Kuroyanagi on the show “Tetsuko no heya”, 1981

What a great piece, Jill. There are still so many I need to see of the great Mifune. Samurai Rebellion may be at the top.